Issue 34

On New-York's Streets, Memory and Slowing Down

I will make no excuses for the faint-hearted: the making of a perfect contact sheet from a processed film is essential.

Jay, Bill; Hurn, David. On Being a Photographer (p. 57).

Ideas for the Creative Mind

This summer I chose to step away from my viewfinder to make a start on the mountain of images that had been waiting patiently for me. For years now I have been a ghost on the streets, drawn to their pulse, their chaos, and the beauty hidden in the ordinary. Yet this way of working has its cost: the negatives pile up faster than I can tend to them.

There was another reason for slowing down, more personal and more fleeting. This is likely the last summer my youngest spends with us before life carries him elsewhere. So we sought out adventures in the Italian Dolomites—where, improbably, a perfect espresso awaits you at 6,500 feet—and in the English Lake District. One landscape long familiar, the other entirely new. I will share more of these wanderings in time, perhaps in the form of a travelogue, a thread I am curious to explore.

Between climbs and long rambles, I turned to the images from my first visit to New York as a photographer rather than a businessman. The work took longer than usual, slowed by the fact that I was experimenting with a new way of handling the negative—the subject of this note.

I

On Being a Photographer by David Hurn and Bill Jay remains one of my touchstones. It imparts wisdom & knowledge without pretence and pares away the excess that clutters so much writing today. Much of how I edit and process negatives can be traced back to its pages.

I begin with simplicity: correctly exposed negatives, flat contrast, minimal sharpening. Modern software makes this easy enough, and my own recipes smooth the path.

This first pass is a culling. Negatives that falter are set aside. Those that hold up are given three stars and no more. These are the frames I am willing to show a client, post to Instagram, or share here. They are also the ones I choose to develop further.

After culling the New York shoot, I was left me with 92 images—out of 700 taken in nine days. It sounds like a lot, but many belong together, linked by time, place, and subject. In these groups, one adjustment often carries to the rest.

Automation plays only a small role for me. I use it where it helps, but I believe a print is a vessel for vision, not an assembly-line product. Others, particularly commercial photographers, may outsource or embed AI deep into their post-production workflow.

II

The second stage is interpretation, where memory and feeling guide my hand, supported by the field notes I keep.

New York, for me, was an act of discovery. I had known it only as a destination for business, never as a place to truly explore. Even now I would not claim to “know” it, but I have walked long enough to sense its optimism, its friendliness and enjoy its light and colours. My notes reminded me how much the rich colour and contrasts struck me—livelier than London, utterly unlike Rome or Lisbon. These impressions shaped how I approached the negatives.

My technical adjustments remain light: a shift in exposure here, a nudge to contrast there. Most of my attention goes to the tone curve, since a print can never hold the full stretch of a digital file. For this series I dodged the shadows and mid-tones, and burned the highlights, tempering the punchy contrasts of the street into something the paper could hold. If a negative resists too much, I let it go.

Colour is my final choice in this stage—what to let sing, what to quieten. It is a small step, but one that changes everything. Over the last year it has become central to my practice, reminding me that tiny shifts often carry the greatest weight.

III

The final stage in preparing negatives is colour grading and sharpening.

Colour grading is how I weave my experience of place and people into the print. Drawing on memory and notes, I tone highlights, mid-tones, and shadows until the image feels like what I lived. This is not science but instinct—a way of leaning into my humanity in a world increasingly drawn to algorithms.

Not everyone favours this approach. But stories thrive on rhythm, texture, and surprise. Without them, they fall flat.

Sharpening comes last, with a light touch applied in two passes: one for the fine details and one for the coarse. Years of practice with my camera and lenses have taught me how far to go, guided by ISO and tonal distribution.

I do this with restraint. Heavy sharpening can ruin skin and texture, a mistake I can’t afford since people inhabit most of my frames. It’s better to tread lightly and make fine adjustments later in print. I’ve learned that if constant heavy sharpening seems necessary, the problem lies in the technique, not the file.

Question

From 92 New York frames, I arrive at 45 with distinct character. I spread them on the light table, adjust where needed, and distil them further into a set of fifteen to thirty for proof printing.

What moves me is not just what I see, but I feel. My art is expressing that in the print. Mine is a craft found in memory, intuition, and the lived moment.

So I wonder: how much of your own work do you shape by memory and feeling, rather than by rule and recipe?

In the Spotlight

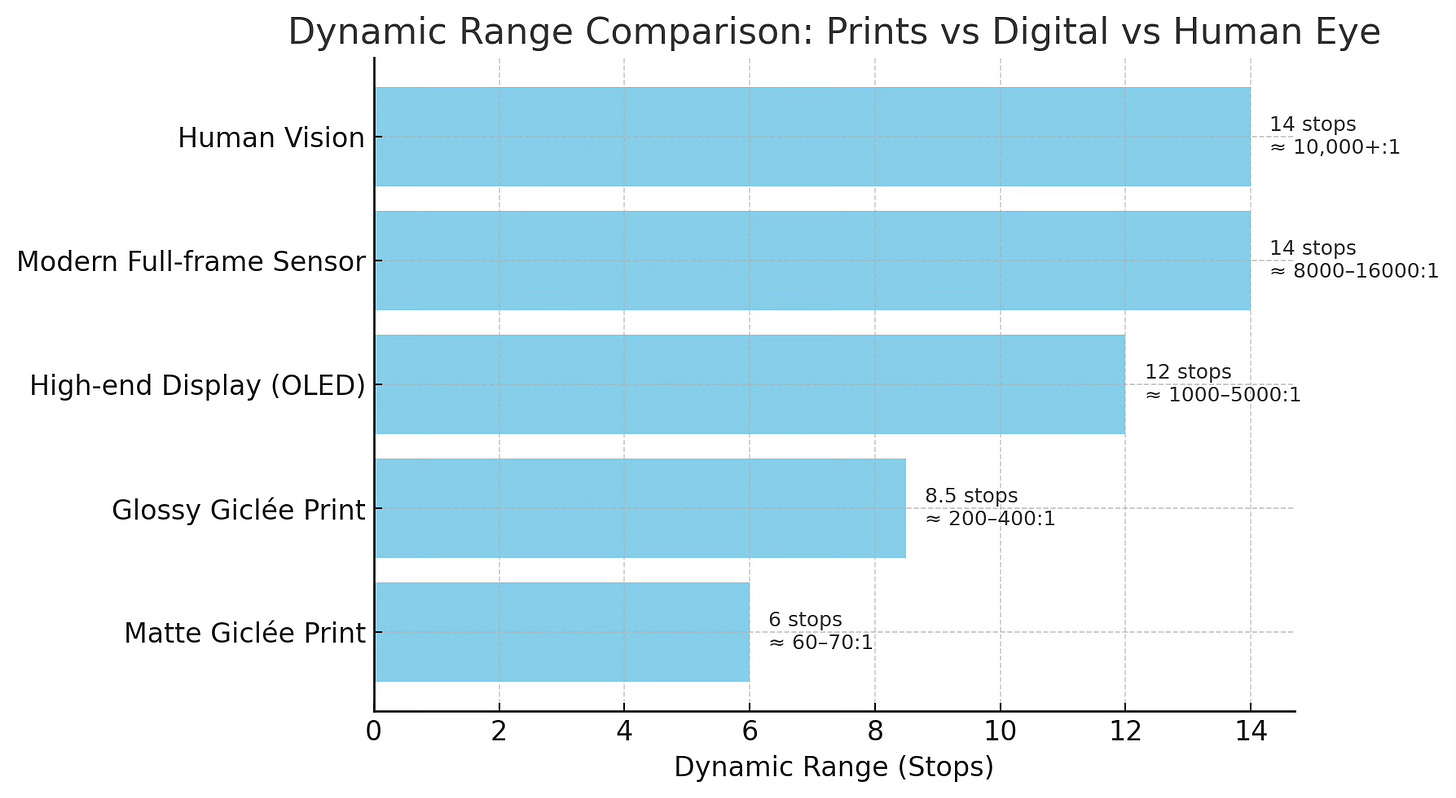

The above infographic sets out the theoretical maximum dynamic range of capture and display devices. I still prefer to measure light in stops, a language of halves and doubles, though today the D-Max ratio is more often quoted.

The challenge is plain: what a sensor records and what a print can carry are worlds apart. Sometimes I lose nearly half the dynamic range in translation. By contrast, high-end displays hold much more of the original image.

I first encountered this puzzle years ago in The Negative by Ansel Adams. His account remains valuable, though for a modern view I often recommend Bruce Barnbaum’s The Art of Photography.

For a glimpse of how this plays out in practice, revisit Issue 32 and the image below of New York’s skyline taken from Roosevelt Island.

The New York series is currently open to advanced enquiries only

That’s a wrap—thanks for reading! As ever, if you know anyone who’s into photography, visual storytelling or collecting finely crafted prints, feel free to pass this email on. Or just hit reply and let me know what you think, say “hi,” or anything else that pops into your mind!